Asteroid alert

TARGETS. Vesta may be the planet that never was, but this crazy diamond is definitely shining on.

Asteroids may not be the most photogenic creatures – someday I want to make a game called “Potato or Asteroid?” – but I find them totally captivating.

Maybe it was watching that asteroid field chase scene in The Empire Strikes Back for the first time as a kid. Or maybe it was learning how one most likely wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Whatever the reason, these tumblers have long occupied a container labeled “exotic, mysterious, and more than a little dangerous” somewhere deep within the cargo hold of my brain.

And that sense has only been reinforced in recent years, as new discoveries grew the solar system’s known asteroid populations well above one million, and we realized just what a busy neighborhood we live in.

I even harbor a secret dream of discovering an asteroid of my own one day – preferably one on track for Earth impact, but with enough time to spare for a successful Bruce-Willis-style rescue, thus averting global disaster. Though that oh-so-modest dream (is it really so much to ask?) may itself soon be going the way of the dinosaurs thanks to a new, industrial-strength generation of sky surveys like the astounding Vera Rubin Observatory, scheduled as of this writing for first light in early 2025. On the plus side, these surveys do make nasty Armageddon-esque surprise extinctions a lot less likely, so that’s always a compensation!

In any case, for the moment I’m a long way from discovering my own asteroid. But I was stoked the first time I noticed the asteroid Vesta popping up in my SkySafari app. Not only was it visible, but it was shining at a magnitude within easy reach for my Seestar S50.

Now, I may be well over 200 years too late to claim rights of first discovery, but when I finally had Vesta framed on my screen (more on that below), and over the following half-hour the majestic diamond etched its unmistakable orbital line across my live stack, I felt just as excited as if I had found an asteroid of my very own.

Favorite facts about Vesta

I originally had only dim recollections of Vesta – possibly related to a NASA mission some years back? Wasn’t quite sure. But a little research revealed a fascinating object with many unique features:

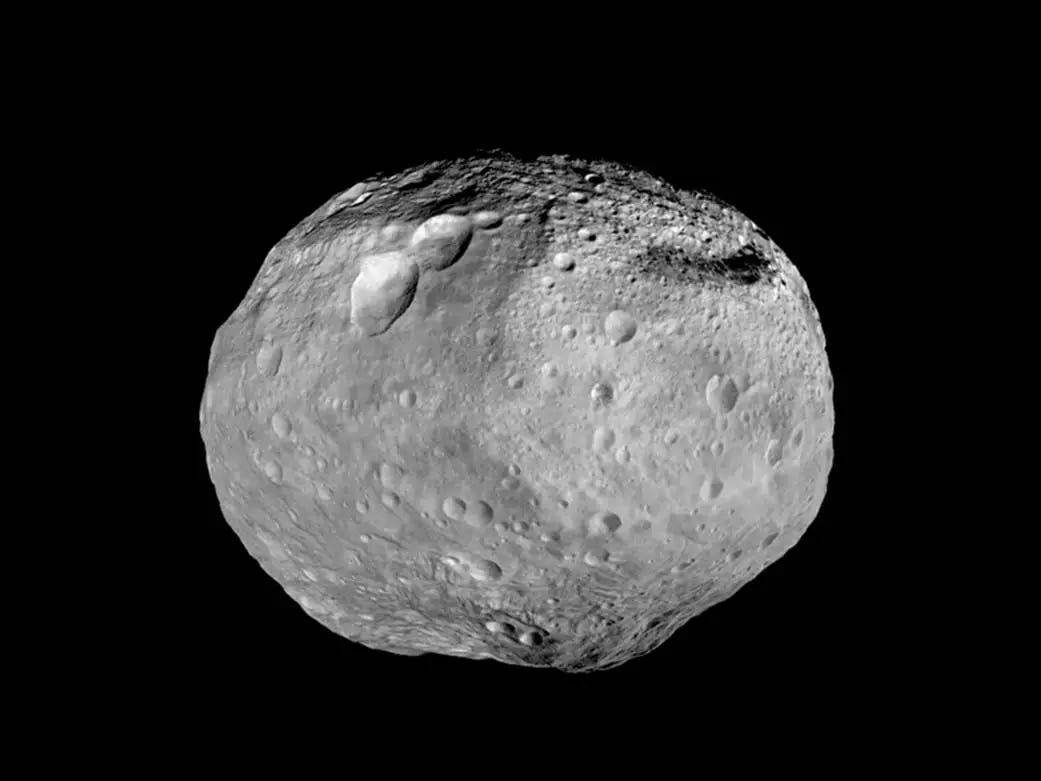

With a mean diameter of 525 km, Vesta’s the second largest resident of our Main Asteroid Belt, that donut of space nestled between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter (though depending on how you choose to see things, it may actually be the largest, since the Belt’s dominant member Ceres was reclassified as a dwarf planet; there seems to be some definitional wiggle room on this).

Vesta’s also the brightest Belt asteroid, and with a dark sky can even be visible to the naked eye.

Thanks to a major smashup something like a billion years ago, Vesta sports one of the solar system’s biggest craters: Rheasilvia, with a central mountain rivaling Mars’ mighty Olympus Mons (I know, crazy, right?!).

And last but not least: Vesta coulda been a contender, but missed out on planethood not once but twice over its checkered career. Firstly, because it’s one of the few remaining known objects in the solar system that originally formed a “differentiated” interior similar to Earth: with a crust, mantle and hot core – a so-called “planetary embryo” – but for reasons did not go on to become a fully-fledged planet. Secondly, because when astronomers originally discovered the first asteroids back in the early 1800s beginning with Ceres, they thought they were looking at additional planets and temporarily labeled them that way. Only later, when they began finding loads more, did they realize these actually represented an entirely new category.

How I looked at it

While Vesta’s bright enough to put it firmly within reach for a typical smart telescope, actually getting it into your frame is another thing. Smart telescope apps are amazing but most tend to have fairly limited catalogs of objects. For example, my Seestar S50’s SkyAtlas does not list Vesta when I search for it. So, now what?

To see Vesta – and really any object not listed in the smart telescope app’s star atlas – we need to do two things: 1) find the coordinates of its current location and 2) load those coordinates into the telescope.

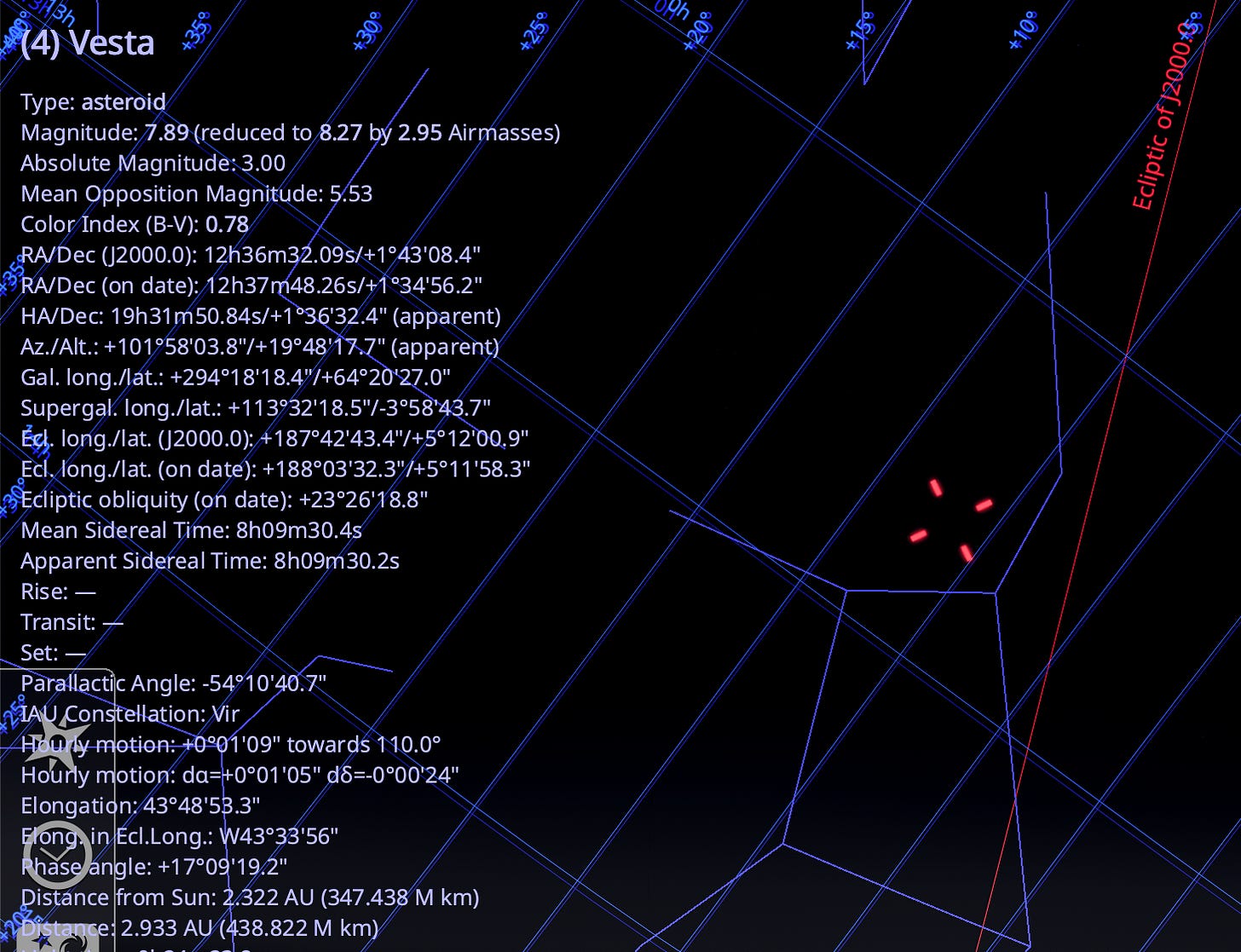

For step 1, I use my favorite planetarium, Stellarium (check out 5 reasons to try Stellarium, the free planetarium for more on this powerful tool). Stellarium has a vastly larger object database than the typical smart telescope app. A quick search brings up Vesta’s position in the sky, along with a trove of real-time data, including its current coordinates in various formats.

With the coordinates in hand, I just need to get them into my telescope. To do that with the Seestar, start in the SkyAtlas main view, then tap the Objects button in the upper right corner (magnifying glass icon).

On the Objects screen, scroll to the bottom, find the My Favorites section, and select the (very well hidden) More > button toward the right.

On the My Favorites screen, tap Customize in the upper right corner.

Now we should be on the Custom Object screen, where we can enter our coordinates. Seester requires RA/Dec coordinates. If you’re not already familiar with these terms, they probably sound like gobbledygook. But RA and Dec are basically just a longitude and latitude for the sky. These coordinates come in different flavors, and the flavor Seestar prefers is JNow, which Stellarium calls RA/Dec (on date). So grab the numbers from this line in Stellarium, and dial them into your Seestar app (NOTE: when entering your Dec, be sure to set +/- correctly. It defaults to -, which can be easy to miss). Make sure you’ve entered ‘Vesta’ in the Name field, then tap the Add button. SkyAtlas will pop a dialog asking if you want to add one more custom object; exit the Custom Object screen by tapping OK.

Back at the My Favorites screen, you should see the custom entry you’ve created for Vesta. Tap the crosshairs icon to the right to return to the SkyAtlas main view. Vesta should now be framed on your screen: a white dot with a handy label. But wait, isn’t that weird – I thought the Seestar didn’t know where Vesta was? Actually, as it turns out, it’s known all along! It just doesn’t have an entry for Vesta in its SkyAtlas search. Well, at least the dot is a nice confirmation we’re in the right spot.

Hit GOTO in the lower right (telescope icon). Voilà!

Final note: since Vesta is a minor planet in motion across the celestial background, its RA/Dec coordinates change continually. Which means your custom entry will soon be out of date and of no use, and there’s no point saving it beyond the current session. Before ending your session for the night, you can delete this entry. Just return to the My Favorites screen, swipe left on the object listing for Vesta, tap the red garbage can icon, and confirm by tapping the Delete button.

Depending on your particular telescope, you should have similar options for manually targeting objects, even if your device’s star atlas does not include them.

Best time to look

Though Vesta is bright enough not to need to be at “opposition” to be visible to smart telescopes, its apparent magnitude does peak during that closest approach. Opposition is when it is nearest to Earth, and you look the opposite direction from the Sun to see the object, which for Vesta happens roughly once every 17 months. Our next opposition with Vesta will be in May 2025.

Bonus points

We know so much about Vesta thanks in large part to NASA’s Dawn mission, which spent more than a year getting up-close-and-personal with the asteroid in 2011-12 before moving on to its sibling Ceres.

NASA’s page dedicated to Vesta.

Did you know?

The impact that carved out Vesta’s Rheasilvia crater also jettisoned vast amounts of debris, and appears to be the source of many meteorites which have since reached Earth.

Given the large quantities of data gathered during the Dawn mission, including detailed geological mapping, plus the fact it’s known to be rich in metals and minerals, Vesta could well be one of the earlier targets when humans ramp up exploration of the Asteroid Belt.

It’s easy to think of asteroids as destroyers, but asteroid collisions also played key roles in the development of Earth as we know it. Impacts likely provided large amounts of the water that makes up our oceans, along with chemical building blocks of life. And even the destructive event that did in the dinosaurs had an upside: who knows, without it we humans might still be small rodent-like creatures, similar to our mammalian ancestors during the Cretaceous.

Finally, I do dig a good sci-fi asteroid field: densely-packed, pirouetting, frequently colliding giant rocks – a boulder ballet – what’s not to love? But though this Hollywood trope is fun, it bears little resemblance to our real Asteroid Belt. While the Belt boasts millions of individual asteroids, they’re actually dispersed across great distances with the gaps between each averaging nearly 1 million kilometers. That’s more than 2.5 times the distance between Earth and Moon!